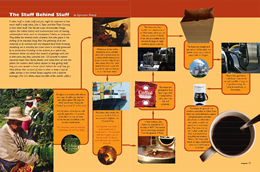

It takes stuff to make stuff, and you might be surprised at how much stuff it really takes.  John C. Ryan and Alan Thein Durning, in their book Stuff: The Secret Lives of Everyday Things, explore the hidden history and environmental costs of making commonplace items, such as newspapers, T-shirts, or computers. They follow the involved chain of events that take place in the making of an everyday thing, from the gathering of its raw materials to its eventual sale and disposal. You’d think throwing something out is wasteful, but more waste is actually generated by its production. According to the authors, in a typical day, Americans throw out about four pounds of garbage each, but in that same day, they consume over 120 pounds in natural resources taken from farms, forests, and mines from all over the planet. The authors don’t expect anyone to stop getting stuff, they just want people to know what’s behind the stuff they get. Here follows their account of what it takes to keep a typical coffee drinker in the United States supplied with a favorite beverage. (The U.S. drinks about one-fifth of the world’s coffee.)

John C. Ryan and Alan Thein Durning, in their book Stuff: The Secret Lives of Everyday Things, explore the hidden history and environmental costs of making commonplace items, such as newspapers, T-shirts, or computers. They follow the involved chain of events that take place in the making of an everyday thing, from the gathering of its raw materials to its eventual sale and disposal. You’d think throwing something out is wasteful, but more waste is actually generated by its production. According to the authors, in a typical day, Americans throw out about four pounds of garbage each, but in that same day, they consume over 120 pounds in natural resources taken from farms, forests, and mines from all over the planet. The authors don’t expect anyone to stop getting stuff, they just want people to know what’s behind the stuff they get. Here follows their account of what it takes to keep a typical coffee drinker in the United States supplied with a favorite beverage. (The U.S. drinks about one-fifth of the world’s coffee.)

To supply one person who drinks two cups of coffee per day for a year (that’s about 700 cups, for which you’ll need 18 pounds of beans), you need 12 coffee trees.

A Colombian coffee farmer will typically apply about 11 pounds of fertilizers to the 12 trees during the year, as well as a few ounces of pesticides.

The pesticides were synthesized in Germany’s Rhine River Valley.

Workers pick the coffee berries by hand and feed them into a diesel-powered crusher, which removes the beans from the pulpy berries that encase them. For each pound of beans, about two pounds of pulp are dumped into Colombian rivers.

The beans, dried under the sun, travel to New Orleans on an ocean freighter in a 132-pound bag.

The freighter was made in Japan and fueled by Venezuelan oil. The shipyard built the freighter out of Korean steel. The Korean steel mill used iron mined in Australia.

The beans are then trucked to a warehouse in an 18-wheeler, which got six miles per gallon of diesel. From there, a smaller truck delivers the bags to neighborhood grocery stores.

The beans are packaged in four-layer bags made of polyethylene, nylon, aluminum foil, and polyester.

In New Orleans, the beans are roasted for 13 minutes at 400ºF. The roaster burns natural gas pumped from the ground in Texas.

The beans are bought and carried out of the store in a brown paper sack, made at paper mills in Oregon.

They’re brought home in the buyer’s car, which burned one-fifth of a gallon of gasoline during the five-mile round trip to the market.

The beans are ground in a machine assembled in China from imported steel, aluminum, copper, and plastic parts, and then placed into a coffeemaker, with water supplied by pipe from a processing plant. The brew trickles into a glass carafe, and then is poured into a mug that was made in Taiwan. (But if you add cream or sugar, you’d have even more connections to follow . . .)